Orlando Int'l Airport's Terminal C Set to Open Following Decades of Planning

Orlando International Airport’s new terminal promises sensations of architecture, endlessly expansive windows, electronic artworks and a luggage system that vaults bags to the top floor to arriving passengers bathed in vacationland sky and agog over Central Florida’s gateway. Terminal C, located four minutes by shuttle train south of original terminals A and B, has billions of dollars of “aesthetic of air, water and sky.” It features the travel grandeur an Emirates business flier might expect and a Disney tourist pinching pennies on Spirit would want to Instagram, all with brewery drafts, better coffee and local foods.

“I think when people see and use Terminal C there are going to be those a-ha moments because it’s pretty spectacular,” said Orlando Mayor Buddy Dyer, the longest serving member of the airport’s authority. If Orlando’s airport ever had a golden era, it would be tough to argue that now is not its dawn.

The new terminal’s 1.8 million square feet will cost nearly $1,800 per square foot, or more than $3 billion in total, possibly the region’s priciest public works job ever. Orlando's new terminal promise to provide 'aha' moments, says the city's mayor, Buddy Dyer.

Spokesperson Carolyn Fennell said that it’s an incomparably costly place in part because it’s embedded with hidden but essential accessories like “a hydrant fueling system for aircraft, a central energy plant, biometric systems at each gate, and an energy distribution system.” Jerky pace With 15 gates, Terminal C opens for the international carriers of Aer Lingus, Azul, British Airways, Caribbean Airlines, Emirates, Gol, Icelandair, Lufthansa and Norse on Sept. 19, and for JetBlue and Breeze a week later.

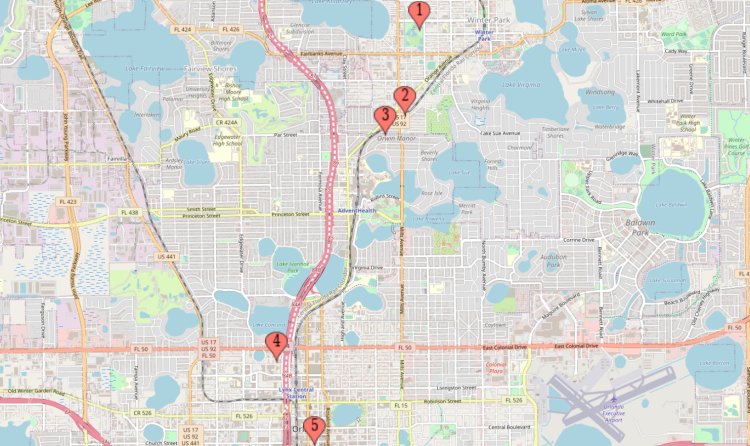

The airport authority expects C, with a huge growth footprint, initially to serve 12 million passengers annually, or a quarter of airport’s total volume. But as shown by its prolonged timeline, the making of Terminal C embodies Orlando International’s repetitious history of two steps forward and a big one back, a jerky pace dictated by booms and busts, the region’s population growth and steady expansions of theme parks. The new terminal, pursued through ups and downs for 30 years and an active project since 2015, was sucker punched by COVID-19. It looks poised this time to recover exuberantly. Viewed from above, the terminal’s design suggests the shape of a jetliner.

The pandemic’s collapse of passengers, flights and airport income brought officials to indefinitely “defer” or chop off the left wing while in early construction. The design of Orlando International Airport's new Terminal C resembles a jetliner from above. The pandemic's financial crunch caused the airport to put the terminal's left wing on hold. (GOAA) The looming shells of four gates were left standing as bare concrete rising from dirt 100 yards apart from each other as workers went on to complete the right wing.

In the pandemic’s fiscal gloom, expertly estimated then to prevail for years, the abandoned structures may have suggested tombs where some of the airport’s fondest dreams went to die. “A lot of the funding sources for Terminal C were based on passenger traffic,” said Kathleen Sharman, the airport’s chief financial officer.

“Back in April 2020 at the low of the pandemic, there were about 1,400 passengers passing through our security checkpoints and normally there are about 70,000 a day,” the CFO said. That was just two years ago and already the airport has reverted to a two-steps-forward phase. “We fell harder than most but we’ve been recovering quite nicely,” Sharman said. $652 million The swift pivot from nearly empty planes early in the pandemic to everyone flying has alienated passengers and humiliated airports and airlines worldwide. But the revenue churn is unmistakable. Orlando International, currently ranking as the world’s seventh busiest, now handles more passengers than during the frothy months just before COVID-19 arrived. The airport’s stores, restaurants and services are pulling in cash like before. The parking garages, critical revenue earners, are rarely less than stuffed beyond their design capacity.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Orlando International’s turnaround is a stealthy flood of financial help from 850 miles away, from Congress, in the form of pandemic assistance and infrastructure stimulus. This is not a figure that airport leaders have ever publicized: $652 million. Amounting to far more than the airport’s annual budget, that’s the total of pandemic and infrastructure grants, some arrived and some to come, the airport has relied on from the federal government.

And there had been hope for more. The airport’s parent, the Greater Orlando Aviation Authority, was awarded a $50 million grant in early July by the Federal Aviation Administration.

“To make sure this is in the right perspective, we did really well,” Sharman said. It was the FAA’s second largest such grant in the nation. But there was disappointment. Airport leaders had applied for a grant of $142 million, intending to spend that money on a project called “Phase 1X Restart” that would put the four deferred gates of the left wing back on a construction schedule. Airport leaders, knowing they might get less and would have to juggle budgets, pulled the trigger earlier this year on a construction restart worth $400 million, which includes rising inflation and the financial hit that comes with resurrecting a mothballed project.

Prior to the pandemic, the new terminal was priced at $3 billion. With pandemic cuts, the figure dropped to $2.8 billion. With the four gates and other elements of the restart, the terminal cost is up to a staggering $3.2 billion. Construction bids for the four gates will be accepted this month. Work will last roughly two years. Difficult situation In June, airport leaders approved terminal cost overruns of $40 million, easily enough to operate a small city for a year.

They reasoned that amount was a pittance for ensuring contractors would finish on time.

“The net total amount of $40 million represents an increase of only 1.4% to the current $2.8 billion budget and is very minor in the context of typical large capital programs,” the airport authority announced in June, referring to the original budget. Making the airport authority look good, by comparison, the Florida Department of Transportation approved $125 million for overruns in its recent overhaul of Interstate 4 through Orlando, upping that project’s cost to $2.4 billion.

Conceivably, the airport’s losses to COVID – lost rents, ticket and airline charges and other revenues – will have been made more than whole by the pandemic relief and the infrastructure stimulus funding. Asked to verify that equation, airport staff did not respond. Orlando’s mayor said he didn’t know. “I can certainly say it eased the pain,” Dyer said.

“I don’t know if it erased all the pain but we would be in a very difficult situation but for the funding.” The airport, run by a public agency and a key jobs hub for Central Florida, has long been buffeted by factors good and bad far outside the control of its leadership. A new terminal became a quest of the Greater Orlando Aviation Authority in the early 1990s, with progress shelved by the 9-11 terror attacks in 2000 that depressed air travel and airport ambitions for several years.

The airport authority resurrected terminal planning but was shut down again during the Great Recession, which took seven years for the airport to shrug off.

Through it all, the region’s population grew from 1 million in 1985, to 2 million in 2005, and to 2.5 million in 2017, and the theme park industry brought on attraction after attraction. From 2015, when the push for Terminal C started for a third time, Orlando International struggled to not drown in its growth, as annual passenger counts rose from 36 million to 50 million in 2019.

The passenger count for 2021, the pandemic’s first full year, plunged to about the same as in the early 1990s, a little more than 20 million. But by late last year, the airport’s rebound was pronounced.

Airport leaders must still determine budgetary juggling to fully fund the restart of the four gates along with a big expanse of tarmac, a huge parking lot for employees, a big station for rental car handling and, as Dyer and others are noting with increased frequency, a redo of the aging terminals A and B.

Much of the funding for the new terminal, in addition to the now complete intermodal station originated from federal budgets in conjunction with state, municipal and private partnerships. Former Congressman and chairman of the House Transportation Committee John Mica, who shepherded much of the federal funding for the airport in recent years, spoke highly of the project's successful conclusion.

Mica first began work on Florida's lagging infranstructure in the 1970s when he acted to secure funds for the "highway to the cow pasture." That highway now serves as the main road to terminals A and B.

Portions of this story were retrieved from the Orlando Sentinel.

Local News Staff

Local News Staff